Personality Vectors

September 13, 2019

Reading Time: about 12 minutes

Overview

Edit 6/4/2020: For firm mathematical footing, please visit Preference Vector 2. I’ve also redacted some of this due to inconsistency after fleshing out the math. I’m leaving this as the more reasonably understandable handwavey explanation. If you enjoy learning from high level ideas then discovering details, read this first and vice versa.

This framework helps to reason about

- What people care about

- Why they do what they do

- What they might do given a situation

Disclaimer

Disclaimer: I use this framework as a retroactive explanation for social interactions. When I interact with people, I first consider how I felt about the interaction, then if I need to explain a concept or [over]analyze a situation, I extrapolate details out to this model.

Overall Framework

Every person has a set of things they care about. People have preferences on everything from appearances to intelligence to dessert interests and favorite movies. You can take these preferences and combine them into a single value/point on a vector. The vector here describes a person’s preferences. Let’s call this the preference vector (pv). A pv is also an accurate reading of what someone cares about and their own tendencies. Put simply, it’s a summary of “who they really are”. I’ve elaborated on how you can combine preferences to a vector in “Creating a Preference Vector”.

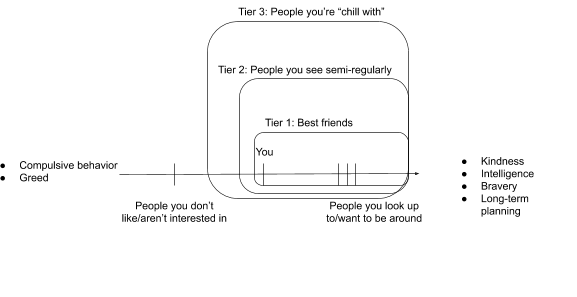

In the example below, I’ve chosen some traits that I admire and desire (right) as well as some I dislike (left). It’s important to note here that, in my opinion, traits aren’t intrinsically better/worse than each other (moral relativism). People (A) tend to be interested in other people (B) they look up to, who (B) have values they (A) appreciate. People (A) want to be with others (B) who are as high up on their (A) vectors as possible, and typically grow distant from those who aren’t. A counterpoint here might be “what about people who welcome diverse individuals”? Then other people who enjoy being around people with vectors that are more different? Then they’ll simply enjoy being around others who have vectors who likely also share this interest in differing values.

One quick note: This image simplifies how values work. The fact that someone has values you enjoy raises where they are on this line, and vice versa. Each value can contribute positively or negatively and this differs from person to person. For a nicer visualization, please check out preference vector 2.

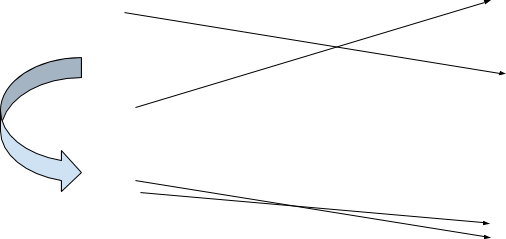

You are the average of your 5 closest friends

What happens when two (or more) people hang out? If the two people discuss and share ideas that are received positively by the other, their vectors begin to converge. Otherwise, the vectors may diverge. Take, for instance, when you share your opinions about your favorite mode of transportation or movie. This influences your friend to consider these factors similarly, as you’ve added supporting evidence for your point of view.

This works out well, since people you care about may further influence your opinions to be improved in ways you’re interested in, but were previously unaware of. This is also why people may seek out their friends advice’ and typically will ask their close friends before asking others who are less close.

Social Competence

The better we are at understanding others’ preferences, the better we are at understanding their motives, actions, and reactions. Being better here is the same as being more socially competent. Unfortunately, we can’t easily discern what people’s pvs are. As we interact more with people, we learn more about their preferences. Some conversations reveal more about their vectors than others (deep conversations vs. small talk), which are in turn helpful for helping you decide if you want to further invest in a person. I think of this as the vector’s opacity. Over time, the line gets more solid. Some people are more open than others. This is how willing someone is to reveal their line (and quickly bolden their lines for others)

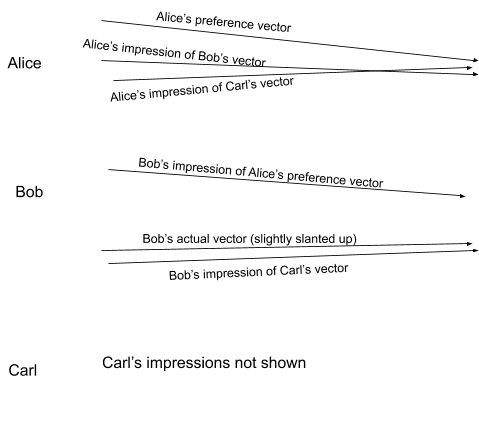

Not only is learning about people’s preference vectors important for understanding social context, understanding other people’s impressions of others (yet again) is crucial as well. This has exponential growth – the number of (perceived/potential) preference vectors = $2^{ppl}$. With 3 people (Alice, Bob, Carl), (AB -> A’s impression of B)

Alice must maintain:

- Alice’s impression of Bob

- Alice’s impression of Carl

- (Alice’s impression of) Bob’s impression of Alice

- (Alice’s impression of) Bob’s impression of Carl

- (Alice’s impression of) Carl’s impression of Alice

- (Alice’s impression of) Carl’s impression of Bob

As we can see here, people’s impressions of each other’s vectors may be inaccurate. Additionally, each person must maintain an image of all vectors that appear here. For instance, Bob has an impression of Carl, but also must maintain his image of what he thinks Alice’s impression of Carl might be. If Bob is significantly closer to Carl and knows that Carl’s actually romantically interested in Alice, he may act differently to adjust for the fact that Alice might not know this. As a result, Bob must maintain

- His impressions of people

- His impressions of other people’s impressions

We are theoretically upper-limit capped at 150 for how many impressions we can maintain before this breaks down. This is Dunbar’s number.

People Change Over Time

Not only do we have impressions of other people’s pvs, we are also figuring out our own. As we learn and grow, our pvs may change significantly. New scenarios (perhaps school drama or a difficult life event) push you to flesh out different areas of their own preference vectors.

Ideal Relationships

People who have complementary personalities work well in relationships. To me, a complementary relationship is one where one’s shortcomings are offset by a positive attribute of the partner. For instance, one person may have anger issues while the other may have exceptional patience and emotional stability to ensure arguments resolve appropriately. This would be represented in this model with two parallel vectors. The two vectors may bounce off each other and possibly influence each other to be closer/more identical, but I don’t think “exact matching vectors” happen in reality, due to the massive variance of upbringings/genetic influences.~~

Creating a Preference Vector

EVERYTHING goes into a preference vector. Here are a bunch of examples on how to map them + how other people’s impressions of your preference vector may change, given an action/event. Feel free to comment if you have other examples you’d like me to cover.

- I enjoy when people do nice things for me

- I respect and want to be around smart people

- My friend took care of me when I was drunk, indicating his loyalty/consideration/helpfulness/responsibility

- He got in a fight over someone shit-talking tiramisu -> I probably don’t want to interact with someone with poor anger management, even though I might like people who are into tiramisu

- I enjoy being around people who can cook -> positive trait

- I cried during the movie -> indicates some form of intimacy/vulnerability to people nearby

Why teaching social competence is difficult

People typically teach social competence with a rule-based approach (bottom up). In scenario A, do this. In scenario B, do something else. For instance, kids who get in trouble for lying are told not to lie as a blanket rule, then left alone to learn what the exceptions are. However, there are far too many rules necessary to navigate a situation. For each relationship (grows exponentially with each additional person), we also have an infinite set of attributes to care about (the attributes that contribute to someone’s pv). With so many variations, we either have too many rules or too many exceptions. It’s far easier to approach learning social nuance from a top-down, statistical approach: “Here’s a ton of data; go find some trends”. The best way to learn about social norms is simply to talk to as many people as possible about as many topics as possible. This also explains why people with troubled childhoods may have less healthy tendencies, since their understanding of how to navigate social situations may be stunted. Kids start caring about/reacting to social norms from a remarkably young age.

Miscellaneous other matchings of social tendencies to this framework:

- “Don’t be judgmental”: A person’s tendency to (a) use an interaction to discern another’s preference vectors, and (b) their tendency to act/make further decisions on whether to invest in the relationship, based off of that interaction.

- “Emotions vs. logic”: Everything goes into preference vectors

- Imo, people are all innately logical, but may weigh things differently. EVERYTHING goes into the preference vector, including “how satisfied would I feel if I react impulsively given my current emotional state”, or “I’m mad right now but logically I know I shouldn’t yell at my kid”. As such, although something might not work out to be the best outcome in the longer term (my kid might have trauma from my yelling), I will have fulfilled something else I have a tendency (albeit possibly unintentionally) – my eagerness to feel instant gratification from exploding anger.

- “Flakes”: New data about another’s preference vector

- People who flake simply have something else they’d prefer to do over spending time with you. You can take this as a signal of what they might think of you, or simply as a signal of what kind of person they are.

- They may have a preference/tendency that leads them to flake, such as anxiety or insecurity. Here, the anxious person can either “be open” – communicate this to Bob, or alternatively it is up to Bob to decide: does this flaking signal Alice’s disinterest in Bob, or her tendency towards other things (anxiety, insecurity, etc?)

- Inaccurate reads on other’s pv’s may also cause flaking. Take for instance if Alice thinks Bob doesn’t enjoy being around Alice, when Bob actually thinks highly of Alice and loves hanging out with her. Alice’s perception of Bob’s perception of Alice may be drastically different from what it actually is, and thus Alice may act accordingly (flake).

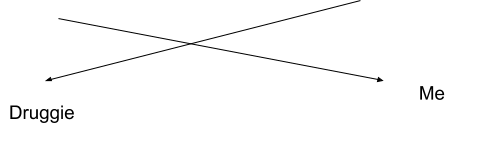

- “Short-term satisfaction”: Differing/opposite preference vectors

- In high school, I was heavily judgemental of people who did drugs. However if I view the world from their pov, they might think of me as similarly lost in the world. They could argue that I was overemphasizing the importance of the long-term, destroying my health by staying up late to study, and not living life in the present. There is no better/worse view here; people are free to have whatever values they like.

- In high school, I was heavily judgemental of people who did drugs. However if I view the world from their pov, they might think of me as similarly lost in the world. They could argue that I was overemphasizing the importance of the long-term, destroying my health by staying up late to study, and not living life in the present. There is no better/worse view here; people are free to have whatever values they like.

- Parenting: Preference vector passing

- People generally believe in their own values, so parenting is often a measure of how good a parent is at passing their pv to their child.

- “Two-faced”: Customizing preference vector appearance

- Some people like to control their image to each person. Although their pv isn’t actually changing, they deliberately reveal a different subset to others. Personally, I’m against doing so. It admittedly has benefits (referrals, generally positive public appearance), but I believe if the end goal is to have a strong, reliable group of close friends, then it is in your best interest to quickly weed out the people who wouldn’t be interested in the “real you” in the first place.

- “Betrayal”: New, different data for your perception of someone else’s preference vector.

- When people are betrayed, it’s really just one person revealing a negative tendency of their preference vector to the other. The ideal scenario here is for the victim to

- Evaluate whether or not they want to further invest

- Evaluate whether they want to forgive

- Decide if/how to give back

- Update their internal model of the betrayer’s preference vector.

- When people are betrayed, it’s really just one person revealing a negative tendency of their preference vector to the other. The ideal scenario here is for the victim to

- “Stubbornness”: How influenceable is their preference vector?

- It’s incredibly difficult to maintain not just our impressions of people, but also other people’s impressions of everyone else. It’s also difficult to “bolden”/learn about other people’s pvs. This leads us to create generalizations that help optimize the way we learn about others. For instance, if every skier I’ve met enjoys moguls, then the next skier might enjoy them as well.

- “In-group vs. Out-group”: Sub-segmentation via. Priority

- When there are too many relationships to keep track of, we prioritize (sometimes arbitrary) subsets of people. Perhaps these are the people you get along better with, you work close to you, or you find attractive. We prioritize learning about their pv’s because time is a finite resource. For instance, people you’re nearby are far easier to hang out with, and therefore have a lower barrier to entry to get to know. Even if they aren’t people you’d typically spend time with, you’re much more likely to elucidate the pv’s of those around you.

Questions for the Reader

- Thoughts/suggestions? Please message me :D

- Do you have a similar framework? Does what was stated here line up with your understanding, or is there anything I’m missing?

- Would you use this? Why or why not?

Relevant Further Reading

If any of this doesn’t make sense, please read Preference Vector 2!