Personality Vectors, Rigidly Defined

June 4, 2020

Reading Time: about 8 minutes

Overview

This establishes a more solid core for personality vectors. If you enjoy learning from the low-level components first, read this first and vice versa.

Core Definitions

Let us establish:

- Things (

$T$): An ordered, infinitely large set of everything you could possibly have an opinion on. - Preference Vectors (

$P$): A person’s preference for each thing they could possibly have an opinion on. This order matches that of$T$. Ex: Honesty. Higher values are better. Two people are more similar if their ($P$s) are more similar. - Attributes (

$A$): A person’s attributes in relation to each thing. Ex: Whether or not I am honest. Higher values are more significant. These can be combined with$P$to determine how much you want to interact with someone.

Preference vectors are actually simply a subset of attributes, but we refer to them separately for simplicity in explanation.

For now, the difference is that preference vectors indicate someone’s opinions towards things and

not their ability to fulfill those things. For instance, I like dogs (preference) but am not a dog (attribute). However, the fact that I like dogs

can also be a separate attribute (since $P \subset A$).

For firm mathematical footing, let’s rigidly define each. We’re working with these vectors in an $l_2$ space.

Notice that a single preference $p_i$ is scaled down to $[-1, 1]$. This means $1$ is the most you could possibly care for any single thing, and everything must exist

in proportion to this. If I have gone through a traumatic experience with a friend with whom I have no other common values, that means I must value “having had that experience”

more than the sum of “all my common values”. The same holds true for attributes.

Similarity

The similarity between two people is the cross product of their PVs. The cross product combines both the significance (length) as well as the similarity (angle).

\[Similarity = \langle P_1, P_2 \rangle\]Bandwidth

Since we have a finite amount of time and processing power, we’re capped in terms of how many things we can have meaningful opinions on. This works like a budget: you have some amount of “effort” you can dedicate towards learning about and participating in things. This “effort” gets distributed across your own attributes as well as your preferences. Effectively, this means it is impossible to care about/be known for everything maximally, although some people may have a more diverse spread than others. Someone who cares a lot about everything might also have a higher “bandwidth” than someone with no opinions.

Opacity

Unfortunately, it’s impossible to know the true value of our preference vectors and attributes, so there’s an extra degree of uncertainty here. As we interact with people, our impressions of them grow more clear, so our perceived attributes and guesses of others’ PVs hopefully grow more accurate.

Example

Suppose our world actually only has 3 things we could possibly have an opinion on: being a dog, being related to Japan, and being honest.

\[T = \{dog, japan, honesty\}\]Let’s first figure out my PV – how much I care about each.

- I like dogs, so

$0.6$ - Japan is an amazing destination with rich culture, so

$0.9$ - Honesty is almost always important, so

0.8

Ordering this up with $T$, we get

Now, I $v$ can also observe how well I adhere to each of these. Note that this is not the same as my preference for them. Rather, it is

how well I am attributed to each.

- I am not a dog, so

$0$ - I have only been to Japan once but don’t know much about their culture, so

$0.2$ - I am mostly honest, but not always, so

$0.6$

I can also observe others’ attributes; Suppose Eve $e$ is my friend who

- is not a dog

$0$ - has never heard of Japan

$-0.2$ - is very honest

$0.8$.

And Bob $b$ is

- a dog

$1$ - that lives in Japan

$0.8$ - but plays tricks and isn’t very honest

$-0.7$.

I can combine each person’s values to respective points on my $P$, which represents my world view.

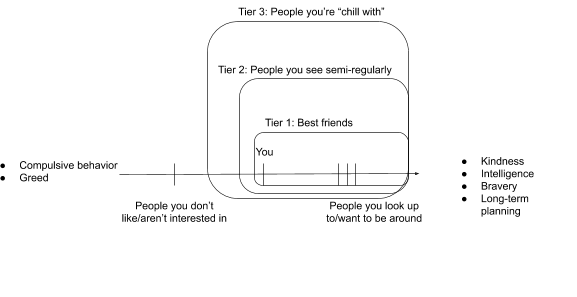

You tend to want to interact with people higher than you on this range and avoid those lower than you on this range.

The formula $f$ for doing so is:

I can also grade myself based on my own attributes $A_v$.

Here, it seems I look up to Bob and will try to spend more time with Bob than Eve.

Other people’s PVs

My preference vector is a reasonable summary of who I am as a person. At the same time, everyone else also has their own preference vectors.

Let’s now describe eve and bob’s preferences.

Eve loves dogs, but has no interest in Japan. She also thinks being honest is pretty important.

On the other hand, Bob is a monster who hates dogs (despite being one), hates Japan (despite living there), and is extremely dishonest.

We tend to want to spend more time with people who have similar preferences. The smaller the inner product between our vectors, the more similar our preferences are. Our preferences are closely tied with our attributes. Over time, people who spend together have preference vectors whose inner products shrink – the vectors become more similar.

In the chart below, we can see that eve (orange) and My (white) PVs are more similar than either of ours is to bob’s. This

means we’re more likely to want to spend time and get to know each other than either of us does to Bob.

Weighted Similarity

It’s important to note that this is a weighted / scaled similarity. Suppose I have 2 friends: X who I have very little in common with but helped me through all my worst times (war, parents dying, dropping out of school, etc.) and Y who shares all my views and morals, but I haven’t had similarly significant experiences with. I might still prefer spending time with X, which means my preference for “having been through significant times” weighs much heavier than “having similar morals”.

More details

- We constrain to an

$l_2$ spaceto allow for infinite-sized preference vectors while keeping the cross product finite. This is important because differences between people must be comparable. Being “infinitely close” to my best friend as well as to my significant other isn’t a meaningful comparison. - Cross product is a combination of length (bandwidth) and angle (similarity). People who have different preferences are obviously different, but so are people with varied bandwidth.

For a more complete list of implications and how this relates to understanding people’s behaviors, read personality vectors!